Foundations of Molecular Generation with GP-MoLFormer on AMD Instinct MI300X Accelerators#

Nearly every technological breakthrough we celebrate begins with a material that did not exist before someone imagined it. Modern computing rests on engineered semiconductors, energy storage depends on carefully designed electrolytes, and sustainable technologies increasingly rely on alternatives to scarce or environmentally costly rare earth elements. Designing such materials with specific properties at scale is one of the most challenging and consequential problems in science.

Generative models promise something that scientists have not traditionally had. They offer a way to explore immense chemical and physical landscapes with something approaching intent, rather than relying solely on slow and expensive trial-and-error experimentation. Teaching machines to imagine molecules or materials is not an abstract exercise; it is an attempt to accelerate the process by which new matter itself is discovered.

In our previous work, we explored this world through the lens of crystalline materials and walked through a complete open source workflow for running the MatterGen model on AMD Instinct MI300X accelerators, from generation to evaluation, without the need for proprietary tools. That experience highlighted the practical importance of open source ecosystems: they allow researchers, university labs, and industry teams to operate on equal footing, to reproduce results, and to build directly on existing work rather than reimplementing closed systems. MatterGen belongs to a class of generative systems that operate directly on the structure of inorganic crystals. It imagines lattices, atomic arrangements, and space group symmetries in three dimensional form, doing for materials science what language models did for text.

But the frontier does not end with crystals. A different class of generative problems emerges in molecular design, where structures are not periodic and where chemical identity is often expressed through symbolic representations such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings [1], fragments, and functional groups. This setting does not replace or supersede crystalline modeling; instead, it reflects a different way of describing matter and a different set of design objectives. GP-MoLFormer [2] enters this space as an open-source model released by IBM, built around a language-model view of chemistry. Rather than operating on three-dimensional lattices, it learns the statistical structure of molecular sequences and uses next-token prediction to explore chemical space. This makes GP-MoLFormer complementary to diffusion-based crystal models like MatterGen, not an alternative motivated by additional complexity, but one shaped by a different representation of molecular structure.

In this blog post, we explore what GP-MoLFormer is and how it approaches the world with a completely different generative philosophy, and we walk through the setup, the environment, and the process of running and generating molecules with it. We look at the scientific problems it tries to solve and how those differ from the ones MatterGen was built for. We examine how these models learn, what their objectives reveal about the domains they inhabit, and why their evaluation metrics cannot be interchangeable.

Overview of GP-MoLFormer#

What GP-MoLFormer is#

GP-MoLFormer [2] is a generative foundation model trained on more than a billion canonical SMILES strings. It is based on the Molecular Language transFormer (MoLFormer) [3] architecture, which demonstrated that a transformer with RoPE and linear attention can learn chemically relevant information that enables it to perform meaningful downstream tasks. GP-MoLFormer reuses these architectural ideas but shifts them into a generative setting, focusing on the ability to sample novel molecular structures rather than classify or regress properties. It is trained entirely on molecular strings, which makes it compatible with large-scale datasets and with hardware setups optimized for sequence models.

Fig. 1 GP-MoLFormer - a generative pre-trained molecular foundation model. (A) Unconditional generation using GP-MoLFormer. SMILES representations are generated autoregressively and randomly along the learned manifold (purple area). (B) During pair-tuning, a prompt vector is learned, which translates a given molecular representation (light blue dots) to an optimized region of the manifold (red diamonds). Figure reproduced from Ross et al. [2] .#

Training objective and architecture#

At its core, GP-MoLFormer is a decoder-only transformer (Fig. 1A) optimized with a causal language modeling objective. Each SMILES token is predicted from the sequence that precedes it, allowing the model to build a statistical understanding of molecular syntax, substructure patterns, and compositional motifs. Linear attention reduces the memory and computational cost of self-attention, making it practical to train the model efficiently on large SMILES corpora and to process longer sequences. Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE) provide a stable and expressive form of relative positional encoding, allowing the model to track long-range token relationships and chemical context within SMILES strings. The model treats molecular generation as a sequence completion problem and, when guided with scaffold constraints - where generation is conditioned on a fixed molecular core - or pair-tuning (described in the following section), can be used effectively for molecular design.

Tasks GP-MoLFormer handles#

GP-MoLFormer supports several forms of molecular generation. It can produce molecules unconditionally by sampling from the learned distribution of SMILES sequences. It can perform scaffold-constrained decoration by extending partial structures without any task-specific finetuning, relying solely on its internal statistical knowledge. It also supports property-oriented molecular design through a method called pair-tuning (Fig. 1B), which uses ordered pairs of molecules to bias the model toward regions of chemical space associated with improved property values.

Evaluation metrics used in GP-MoLFormer#

GP-MoLFormer is assessed using the MOSES benchmark [4] along with MoLFormer-based embedding metrics, giving a multi-angle view of how well the model reproduces chemical patterns, explores new structures, and maintains internal diversity. The core MOSES metrics include Frag (fragment similarity), Scaf (scaffold similarity), and SNN (similarity to nearest neighbor), all of which measure how closely the generated set reflects structural motifs in a reference dataset. Diversity is captured through IntDivp, which quantifies pairwise dissimilarity within the generated molecules, while FCD evaluates global distributional similarity using ChemNet embeddings. MoLFormer-based metrics mirror these but use MoLFormer embeddings instead: FMD (Fréchet MoLFormer Distance) and DNN (nearest-neighbor embedding distance).

Beyond similarity and diversity, GP-MoLFormer is evaluated on validity, uniqueness, and novelty, which together characterize the chemical soundness and generative reach of the model. Validity measures the fraction of syntactically correct SMILES, uniqueness measures the proportion of distinct molecules at a fixed sample size (e.g., Unique@10k), and novelty measures how many generated molecules do not appear in the training set. The authors also analyze scaffold novelty distributions, showing that despite the large training corpus, the model generates a substantial tail of unseen scaffolds. Temperature-controlled sampling experiments demonstrate how novelty, validity, and uniqueness trade off as sampling entropy increases. Finally, the authors report a scaling law for novelty, indicating that novelty decays approximately exponentially as the number of generated molecules grows. This behavior is consistent with large generative models approaching saturation of the underlying chemical space. Readers interested in the exact mathematical definitions, formulas, and additional diagnostic plots can find them in the Additional Resources.

Molecules vs. Crystals: Two Very Different Generative Problems#

Molecular generation and crystalline materials design fall under the broader umbrella of materials discovery, but they operate on fundamentally different representations and constraints. Molecular design typically works with discrete symbolic descriptions, such as SMILES strings, where chemical identity is defined by connectivity, functional groups, and local bonding rules. This makes it natural to frame molecule generation as a sequence modeling problem, where autoregressive language models learn how valid chemical structures are composed token by token. GP-MoLFormer is an example of this approach, operating entirely in the space of molecular strings and large-scale symbolic datasets.

Crystalline materials, by contrast, are defined by periodic three-dimensional structures. Their validity depends on atomic coordinates, lattice vectors, and crystallographic symmetry, as well as on whether the resulting structure corresponds to a physically stable configuration after relaxation. Generative models in this setting must operate directly in continuous geometric space and respect physical invariances and energetic constraints. MatterGen exemplifies this class of models, using diffusion-based generation to propose full crystal unit cells that can be evaluated in terms of thermodynamic stability and novelty. While both molecular and crystalline generation aim to explore vast design spaces, the differences in data, objectives, and evaluation criteria naturally lead to different modeling choices.

With this context in place, we now turn from conceptual differences to practical usage. In the following sections, we walk through the environment setup on AMD GPUs and demonstrate how to run GP-MoLFormer for molecular generation in different modes. This moves the discussion from architectural ideas to concrete steps that allow the model to be used in practice.

Installation and Setup#

0. Requirements#

AMD GPU: See the ROCm documentation page for supported hardware and operating systems.

ROCm kernel-mode driver: As described in Running ROCm Docker Containers need to install amdgpu-dkms.

Docker: See Install Docker Engine on Ubuntu for installation instructions.

AMD Container Toolkit: See Quick Start Guide for installation and corresponding ROCm blog.

1. Clone ROCm-blogs Repository#

Clone ROCm-blogs repository and navigate to the GP-MoLFormer blog directory:

git clone https://github.com/ROCm/rocm-blogs.git

cd rocm-blogs/blogs/artificial-intelligence/gp-molformer

Follow the next setup steps from this directory.

2. Docker Container#

Docker image: rocm/pytorch:rocm7.0_ubuntu22.04_py3.10_pytorch_release_2.7.1

Run the Docker container with the AMD Container Toolkit (recommended). This command selects specified AMD GPUs, set as AMD_VISIBLE_DEVICES environment variable accordingly.

docker run -d \

--runtime=amd \

-e AMD_VISIBLE_DEVICES=0,1,2,3 \

--name molformer \

-v $(pwd):/workspace/ \

rocm/pytorch:rocm7.0_ubuntu22.04_py3.10_pytorch_release_2.7.1 \

tail -f /dev/null

The number of visible GPUs is configurable. Multiple GPUs are useful for pair-tuning and other training workloads, where distributing batches can significantly reduce wall-clock time. For inference and molecule generation, a single GPU is sufficient, and users can set AMD_VISIBLE_DEVICES accordingly (for example, AMD_VISIBLE_DEVICES=0).

Enter the interactive session and continue with the setup:

docker exec -it molformer bash

Clone the official gp-molformer repository and apply the patch we’ve provided to fix the implementation for newer version of transformers.

cd /workspace

git clone https://github.com/IBM/gp-molformer.git

cp /workspace/src/pairtune_training.patch /workspace/gp-molformer/

cd /workspace/gp-molformer

git apply pairtune_training.patch

Install environment requirements:

pip install -r /workspace/src/requirements.txt

Note

The optional fast_transformers dependency used by GP-MoLFormer is not available in this environment. When it is not present, the code automatically falls back to the standard PyTorch transformer implementation, which works correctly on ROCm.

Inference#

Unconditional Generation#

cd /workspace/gp-molformer

python scripts/unconditional_generation.py --num_batches 1 uncond.csv

This command samples molecules directly from the model without any conditions or prompts. The script writes a CSV file (uncond.csv) containing 1,000 SMILES strings, each representing a molecule drawn from the learned distribution. These structures span a wide range of fragments, scaffolds, and functional groups, reflecting the chemical patterns the model absorbed during pretraining. Below are a few examples from the output:

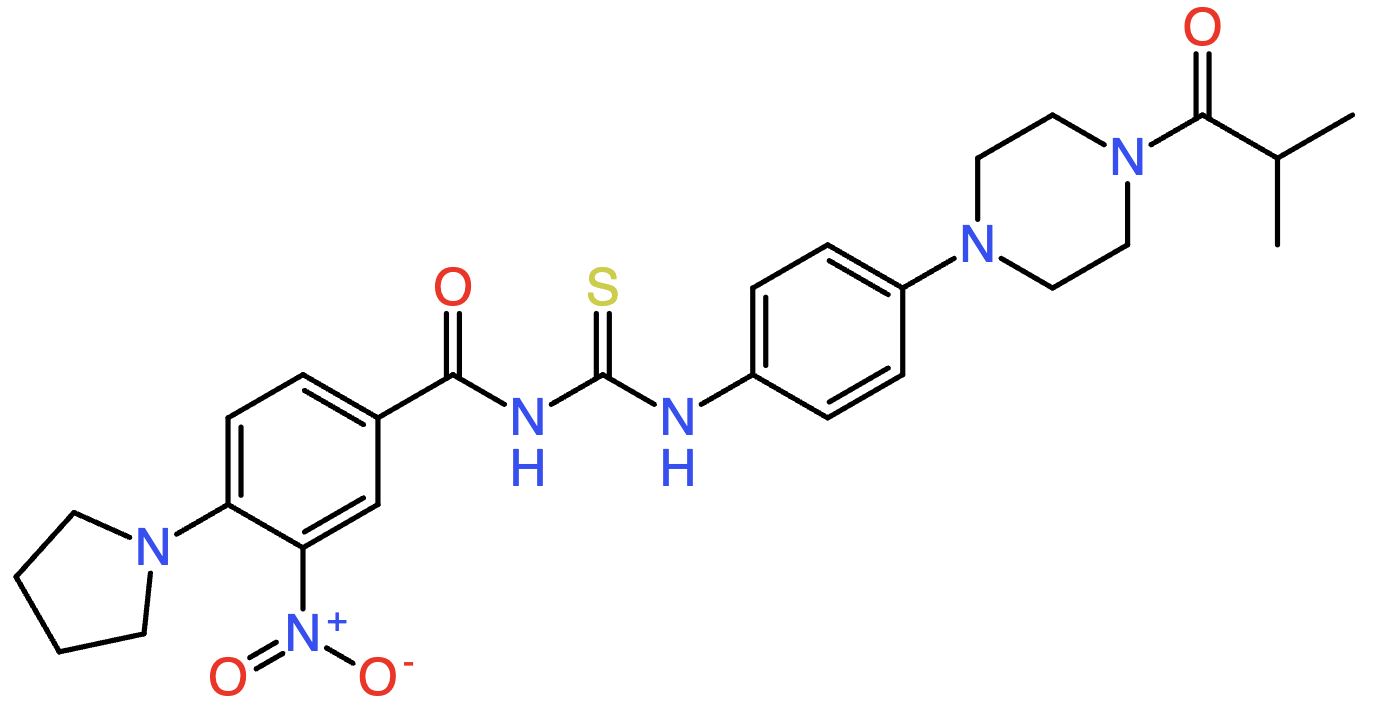

CC(C)C(=O)N1CCN(c2ccc(NC(=S)NC(=O)c3ccc(N4CCCC4)c([N+](=O)[O-])c3)cc2)CC1

O=C(CN1C(=O)C2CCCCC2C1=O)Nc1ccc(S(=O)(=O)Nc2ccc(Cl)cc2)cc1

CC(C(=O)N1CCCC2(CCN(C(=O)C3(F)CN(C(=O)OC(C)(C)C)C3)CC2)C1)n1cccn1

COCCN(C)C(=O)c1nnc2n1CCN(C(=O)c1nnsc1C)C(C)C2

CC(C)(CCC(=O)OC(C)(C)C)NC(=O)Cn1c(O)nc2ccccc21

You can inspect or filter uncond.csv to explore the chemical space the model generates.

We can visualize the molecular structure corresponding to the SMILES string (see Additional Resources). For example, the first SMILES string in the list corresponds to the following molecule (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2 Visualization of the molecule represented by the SMILES string CC(C)C(=O)N1CCN(c2ccc(NC(=S)NC(=O)c3ccc(N4CCCC4)c([N+](=O)[O-])c3)cc2)CC1.#

Conditional Generation#

cd /workspace/gp-molformer

python scripts/conditional_generation.py c1cccc

This script performs scaffold-constrained generation, where the model completes or elaborates a user-provided SMILES fragment. In this example, the fragment c1cccc represents a simple aromatic ring pattern, and the model generates molecules that preserve this scaffold while exploring different substitutions and extensions. The script reports how many valid and unique molecules were produced and prints a small sample of the generated SMILES. For the command above, GP-MoLFormer generated 653 valid molecules, of which 649 were unique, for example:

Total number of successful molecules generated is 653

Total number of unique molecules generated is 649

...

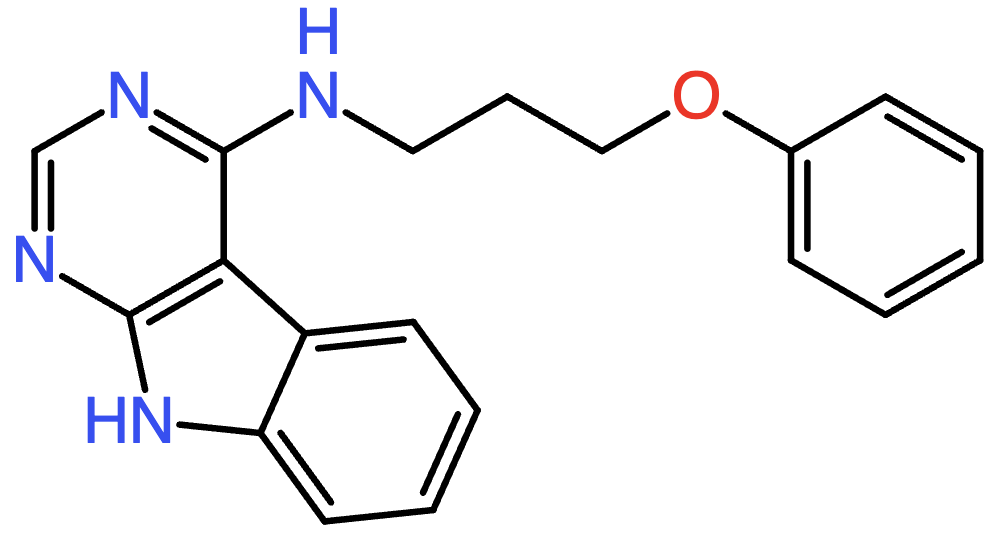

c1cccc(OCCCNc2ncnc3[nH]c4ccccc4c23)c1

c1cccc(-c2cccc(-c3cccc(-n4c5ccccc5c5cc(-c6ccc7c8ccccc8n(-c8ccccn8)c7c6)ccc54)c3)c2)cc1

c1cccc(-c2nc3sccn3c2CNCC2CC3CC3C2)c1

c1cccc(C2(c3noc(CCc4ccc5[nH]ccc5c4)n3)CCC2)c1

...

These outputs show how the model expands the initial ring into more complex molecules while keeping the original scaffold intact. This mode is useful when you want to explore chemical space around a core structure or generate analogs of a known motif.

By visualizing SMILES strings, we can observe the molecular structures they represent. For example, the first SMILES string in the list corresponds to the following molecule (Fig. 3):

Fig. 3 Visualization of the molecule represented by the SMILES string c1cccc(OCCCNc2ncnc3[nH]c4ccccc4c23)c1.#

Training#

Pair-tuning#

Pair-tuning is GP-MoLFormer’s mechanism for guiding the generative model toward molecules with improved property values. Instead of training on absolute property values, the model is trained on ordered pairs of molecules, where each pair encodes a directional preference: molecule B has a higher value of the target property than molecule A. During training, the model learns a prompt vector that shifts its generative distribution toward molecules with improved properties (Fig. 1B). This approach avoids retraining the entire transformer and allows GP-MoLFormer to adapt quickly to different optimization targets such as QED (drug-likeness), penalized logP, and DRD2 binding affinity, all of which are available in the data/pairtune/ directory.

A pair-tuning run can be launched as follows:

cd /workspace/gp-molformer

python -m scripts.pairtune_training qed --lamb

Training duration and batch size can be adjusted as needed. For example:

cd /workspace/gp-molformer

python -m scripts.pairtune_training qed --lamb --eval_epochs 10 --num_epochs 100 --batch_size 1200

When pair-tuning finishes, the training script writes a new adapter checkpoint into a directory such as: models/pairtune/qed/checkpoint-740/. This folder contains the lightweight components learned during tuning - primarily adapter_model.bin and adapter_config.json - along with metadata files such as trainer_state.json, optimizer.pt, scheduler.pt, and tokenizer mappings. These files do not duplicate the full GP-MoLFormer weights; instead, they store only the small prompt-tuning parameters that modify the base model’s behavior for the chosen property. During training, periodic evaluation logs report metrics such as validity, uniqueness, and the change in the target property for generated samples. These numbers help monitor training progress and indicate whether the adapter is beginning to influence the generative output. After training completes, the resulting checkpoint can be loaded alongside the base GP-MoLFormer model to generate molecules conditioned by the tuned prompt.

Summary#

In this blog, we explored GP-MoLFormer as an open-source foundation model for molecular generation and showed how its sequence-based architecture enables efficient large-scale exploration of chemical space on AMD GPUs. We positioned it alongside MatterGen to clarify how molecular and crystalline design differ in data, structure, and scientific objectives, and why each domain demands its own modeling paradigm. We walked through the steps required to set up the environment, run inference for unconditional and scaffold-guided generation, and apply pair-tuning for property-oriented molecular design. By the end of this guide, readers should have both a conceptual understanding of GP-MoLFormer’s role in molecular discovery and a practical workflow for generating molecules using fully open-source tools on AMD hardware. There is much more to explore in this space, so stay tuned for what comes next.

Acknowledgments#

We thank Rahul Biswas, Luka Tsabadze, Pauli Pihajoki, Baiqiang Xia, and Daniel Warna for their contributions through technical discussions, reviews, and hands-on support.

References#

[1] David Weininger, SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules, J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 28 (1) (1988) 31–36.

[2] Ross, J., Belgodere, B., Hoffman, S. C., Chenthamarakshan, V., Navratil, J., Mroueh, Y. & Das, P. (2024). GP-MoLFormer: A Foundation Model for Molecular Generation. arXiv:2405.04912 [q-bio.BM]. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2025/dd/d5dd00122f

[3] Ross, J., Belgodere, B., Chenthamarakshan, V., Padhi, I., Mroueh, Y. & Das, P. (2021). Large-Scale Chemical Language Representations Capture Molecular Structure and Properties. arXiv:2106.09553 [cs.LG]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.09553

[4] Polykovskiy, D., Zhebrak, A., Sanchez-Lengeling, B. et al. (2018). Molecular Sets (MOSES): A Benchmarking Platform for Molecular Generation Models. arXiv:1811.12823 [cs.LG]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1811.12823

Additional Resources#

Accelerating AI-Driven Crystalline Materials Design with MatterGen on AMD Instinct MI300X

GP-MoLFormer GitHub Repository

Disclaimers#

Third-party content is licensed to you directly by the third party that owns the content and is not licensed to you by AMD. ALL LINKED THIRD-PARTY CONTENT IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT A WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. USE OF SUCH THIRD-PARTY CONTENT IS DONE AT YOUR SOLE DISCRETION AND UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES WILL AMD BE LIABLE TO YOU FOR ANY THIRD-PARTY CONTENT. YOU ASSUME ALL RISK AND ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY DAMAGES THAT MAY ARISE FROM YOUR USE OF THIRD-PARTY CONTENT.