GEAK HIP: Expanding GEAK for HIP Code Optimization#

This blog discusses the use of the Generating Efficient AI-centric Kernels (GEAK) agent for automated HIP code optimization, demonstrating how GEAK’s agentic pipelines can elevate customer and developer code and boost AI performance on AMD platforms.

Key Takeaways:

Announcing the GEAK expansion to HIP code optimization, enabling AI agents to refine HIP kernels with frontier LLMs for superior efficiency.

Announcing dedicated HIP code evaluation examples, demonstrating improvements across kernels from basic AMD ROCm™ and MMCV operations, achieving 1.08x and 1.20x average speedups on these benchmark sets.

For practical customer-facing bottlenecks in Voxelization and SwiGLU, the agent achieved 2.07x and 1.68x speedups, superior to engineers’ manually optimized versions.

For GEMM heuristic rule optimization, the agent generated heuristic rules achieving an average of 1.28x speedup compared to handwritten rules.

Building on our GEAK framework (GEAK — ROCm Blogs), originally introduced for generating Triton kernels from high-level instructions, we are now extending GEAK to optimize existing HIP code, transforming baseline HIP implementations into highly efficient versions tailored for AMD hardware, including the AMD Instinct™ MI300 series GPUs.

The HIP kernel language is a CUDA-like C++ dialect for writing GPU kernels that run on AMD hardware while remaining portable to NVIDIA GPUs. It supports single-source C++ features, allowing developers to build code that is both portable and high-performance. Well-optimized HIP kernels are critical for achieving substantial speedups in demanding AI workloads—poorly tuned code can become a bottleneck, while refined implementations deliver significant gains in latency, throughput, and resource utilization on modern hardware.

While GEAK’s initial focus on Triton excelled at creating kernels from textual descriptions, adapting it for HIP optimization involves key modifications: handling pre-existing code as input, incorporating HIP-specific syntax in instructions, cultivating a compile/debug pipeline, and emphasizing iterative refinement for latency reduction rather than from-scratch generation. We also invite readers to explore the newly introduced GEAK-Triton v2 framework, which extends the GEAK family with advanced Triton kernel optimization support with additional hardware-aware feedback loops.

HIP Kernel Optimization GEAK Framework#

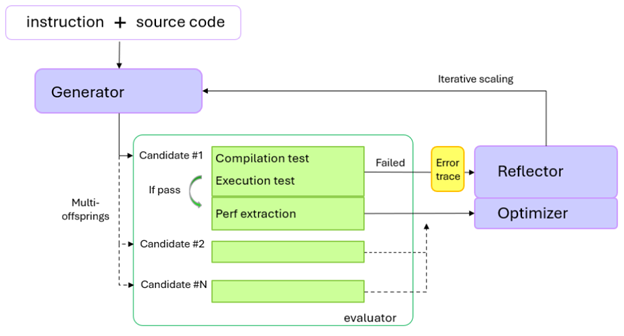

Figure 1: Overview of the GEAK agent for HIP code optimization.#

As shown in Figure 1, the agentic AI system for the HIP kernel optimizer is essentially the same as the original Triton generation framework. The main changes in the HIP kernel optimization framework are as follows:

Generator: Takes instructions and functional source HIP code as input, and outputs potentially optimized code.

Evaluator: Performs in-place replacement of the targeted kernel file and conducts compilation, execution, and performance extraction. Error traces are gathered during compilation and execution. If no errors occur, the extracted performance metrics and code are sent to the optimizer to generate further optimization directions.

Reflector: Activates when the evaluator fails to compile or execute the generated kernel code, or when performance or validation metrics are not extracted correctly during unit tests.

The number of multiple offspring can be configured from 1 to N, determining how many optimized code variants the generator produces simultaneously. Note that increasing this number significantly slows down the overall generation process, as the same iterative scaling factor controls the number of iterations each optimized code variant undergoes in the generator.

Additionally, the composable and configurable techniques mentioned in the previous blog on Triton kernel generation also apply to the HIP kernel optimization.

HIP optimization examples and case studies#

This section presents a collection of HIP optimization examples and case studies, demonstrating how GEAK can be applied across different contexts—from introductory kernels to real-world industrial bottlenecks. Each case highlights the workflow, performance gains, and required adaptations when using GEAK.

ROCm examples – illustrative kernels demonstrating the basic usage of GEAK in HIP optimization.

MMCV examples – adapted from the widely used computer vision repository MMCV, featuring 10 kernels optimized using GEAK.

Case study #1: Voxelization – a customer-provided kernel with hardware bottlenecks, where GEAK achieved superior performance compared to hand-tuned kernels.

Case study #2: SwiGLU – another customer bottleneck kernel optimized by GEAK, showing performance gains over manually engineered solutions.

Case study #3: GEMM heuristic – demonstrates GEAK applied to heuristic routines in C++/HIP, focusing on hyperparameter selection for GEMM workflows.

For the system configuration of the above examples, please refer to the Endnote section.

To try the following examples, please refer to the GitHub repository: AMD-AGI/GEAK-agent:GEAK-HIP.

ROCm examples#

We include simple applications from the ROCm Examples repository [1] to show basic optimization techniques. The ROCm examples repo is designed to help new users get started with ROCm software and offers advanced samples for experts. We use our agent here to show how GEAK improves speed and efficiency in these examples.

For this task, we utilized the original C++ unit test code within the all-in-one HIP code file and added the performance evaluation to the original code to check both accuracy and speed.

List of examples from the ROCm examples repository:

bitonic_sort, convolution, floyd_warshall, histogram, monte_carlo_pi, prefix_sum

The results are shown in the table below:

Model |

Agent offsprings |

MAX Speedup |

AVG Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

GPT-5 |

2 |

1.20x |

1.08x |

GPT-5 |

1 |

1.14x |

1.04x |

Table 1: Evaluation of GEAK OptimAgent on 6 ROCm-examples, the MAX Speedup is the maximum speedup (latency ratio) of the original HIP code latency vs. optimized HIP code latency. AVG Speedup averages the speedup of all ROCm-example kernels.

MMCV examples#

We extracted the MMCV kernels from the MMCV repository [2]. MMCV is the foundational computer vision library from OpenMMLab, providing core functionality for image and video processing, data transforms, CNN architectures, visualization, and efficient CPU/GPU operations. It integrates deeply with PyTorch and serves as the backbone for downstream toolkits such as MMDetection and MMSegmentation. Many of its unit tests leverage PyTorch bindings and compare results against PyTorch operations.

We modified the unit tests to compile and load the HIP kernels via PyTorch extensions. Accuracy and speed were verified using Python code with PyTorch. The original unit tests focused on validation with minimal input sizes, which did not fully reflect kernel latency under typical conditions. We expanded the input sizes slightly to better represent latency in practical usage. Accuracy was validated by comparing the results of the original HIP code against those of the GEAK-generated HIP code.

List of examples from the MMCV repository:

assign_score_withk, ball query, furthest_point_sample, gather_points, knn, points_in_box, roi aware_pool3d, roipoint_pool3d, three_interpolate, three_nn

The results are shown in the table below:

Model |

Agent offsprings |

MAX Speedup |

AVG Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

GPT-5 |

2 |

2.15x |

1.20x |

GPT-5 |

1 |

1.82x |

1.12x |

Table 2: Evaluation of GEAK OptimAgent on 10 MMCV kernels.

Case Study #1: Voxelization#

Here, we break down the optimization of voxelization, recognizing it as an important user case for comparing agent-generated code with the original implementation. The voxelization operation groups 3D point cloud points with identical integer (x, y, z) coordinates into voxels, reducing data density for efficient neural network processing. Rooted in computer vision and robotics, voxelization is essential for LiDAR data processing in autonomous vehicles via frameworks such as PointPillars and MMCV. This operation typically applies to quantized sensor data (e.g., LiDAR and depth cameras), enabling sparse convolutions for real-time object detection, segmentation, and scene understanding.

The GEAK agent discovered and optimized the following aspects of the original MMCV implementation, ensuring validation correctness for the local index of each point within its voxel group:

Caching: Predecessor points’ coordinates (x, y, z) and validity flags are cached in shared memory (LDS) per tile, avoiding repeated global memory fetches for each thread’s scan.

The agent optimized code block is written as follows:

// Use shared memory as a tile cache for predecessor coordinates (x,y,z) when NDim==3 extern __shared__ int4 smem_xyzv[]; // x,y,z,valid_flag ... // Coalesced loads into LDS; pack validity as .w if (load_idx < num_points) { const int base = load_idx * 3; const int x = coor[base + 0]; const int valid = (x != -1); const int y = valid ? coor[base + 1] : 0; const int z = valid ? coor[base + 2] : 0; smem_xyzv[threadIdx.x] = make_int4(x, y, z, valid); } else { // out-of-bounds: mark as invalid smem_xyzv[threadIdx.x] = make_int4(-1, 0, 0, 0); } __syncthreads();

Parallelism: Threads in a block cooperatively load tile data in parallel (coalesced accesses); each thread scans its own predecessors independently but synchronized via barriers.

The agent optimized code block is written as follows:

const int load_idx = tile_start + threadIdx.x; ... smem_xyzv[threadIdx.x] = make_int4(...); __syncthreads();

Tiling: Breaks the point list into block-sized chunks, processing one tile at a time in shared memory to minimize global traffic.

The agent optimized code block is written as follows:

for (; l + 8 <= ub && !done; l += 8) { int4 v0 = smem_xyzv[l + 0]; int4 v1 = smem_xyzv[l + 1]; ... if (v0.w && v0.x == coor_x && v0.y == coor_y && v0.z == coor_z) { num++; ... } if (!done && v1.w && v1.x == coor_x && v1.y == coor_y && v1.z == coor_z) { num++; ... } ... }

ILP (Instruction-Level Parallelism): Unrolled loops allow multiple comparisons per cycle, overlapping operations for better throughput.

Occupancy: launch_bounds hints limit registers/block, enabling more blocks/SM for higher GPU utilization.

Early Exits: Stops scanning once max_points reached or no more predecessors, saving cycles.

The results are shown in the table below:

Optimization Method |

Speedup Ratio |

|---|---|

GEAK Agent optimized |

2.07x |

Manually optimized by kernel engineer |

1.84x |

Table 3: Evaluation of OptimAgent on voxelization kernel. The agent-optimized speedup compares the performance with the kernel engineer’s result.

Overall, the GEAK agent managed to produce an optimized version of the code that has achieved 2.07x speedup, exceeding the performance gains from manual optimization.

Case Study #2: SwiGLU#

The SwiGLU (SiLU-Gated Linear Unit) activation, introduced by Shazeer (2020) [3], has become a key building block in modern transformer architectures. Instead of a single nonlinear activation, SwiGLU splits the feed-forward input into two branches: one passes through a SiLU activation; the other remains linear, and the two are combined by elementwise multiplication. This design improves gradient flow and expressiveness compared to ReLU or GELU and is now widely adopted in large language models such as LLaMA, Qwen, and DeepSeek, where it plays a critical role in boosting training stability and downstream performance.

In practice, implementing SwiGLU requires large matrix multiplications (the linear projections) followed by a lightweight activation and gating step. Here, we focus on the latter: applying SiLU(x) * y after the GEMMs, which can still become a bottleneck if not optimized for GPU memory access and parallelism.

We tackled this performance challenge on the AMD Instinct MI308x platform. The GEAK agent discovered and optimized the following directions from the original implementation in vLLM [4]:

Vectorization: Processes data in bf16x2 pairs and uint4 (128-bit) groups for wider, coalesced loads/stores.

The agent optimized code block is written as follows:

const __hip_bfloat162* __restrict__ row_x2 = reinterpret_cast<const __hip_bfloat162*>(row_x); const __hip_bfloat162* __restrict__ row_y2 = reinterpret_cast<const __hip_bfloat162*>(row_y); __hip_bfloat162* __restrict__ row_o2 = reinterpret_cast< __hip_bfloat162*>(row_o); const uint4* __restrict__ row_x4 = reinterpret_cast<const uint4*>(row_x2); const uint4* __restrict__ row_y4 = reinterpret_cast<const uint4*>(row_y2); uint4* __restrict__ row_o4 = reinterpret_cast< uint4*>(row_o2); for (int64_t base_p = (int64_t)t * 4; base_p < bulk_pairs; base_p += tile_stride_4p) { ... __hip_bfloat162 x2_0 = *reinterpret_cast<const __hip_bfloat162*>(&lx.x); __hip_bfloat162 y2_0 = *reinterpret_cast<const __hip_bfloat162*>(&ly.x); float2 fx0 = __bfloat1622float2(x2_0); float2 fy0 = __bfloat1622float2(y2_0); fx0.x = silu_f(fx0.x) * fy0.x; fx0.y = silu_f(fx0.y) * fy0.y; __hip_bfloat162 o2_0 = __float22bfloat162_rn(fx0); // (similar pattern for each part for o2) }

Alignment Handling: Checks 16B alignment for the optimized bulk path with 128-bit vector I/O; fallback to paired unrolled loops.

The agent optimized code block is written as follows:

const bool aligned16 = ((reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(row_x2) % 16u) == 0) && ((reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(row_y2) % 16u) == 0) && ((reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(row_o2) % 16u) == 0); if (aligned16) { // Use 128-bit vectorized path ... } else { // Fallback scalar bf16x2 loop for (; p < num_pairs; p += stride) { __hip_bfloat162 x2 = row_x2[p]; __hip_bfloat162 y2 = row_y2[p]; float2 fx = __bfloat1622float2(x2); float2 fy = __bfloat1622float2(y2); fx.x = silu_f(fx.x) * fy.x; fx.y = silu_f(fx.y) * fy.y; row_o2[p] = __float22bfloat162_rn(fx); } }

Fast math intrinsics: Uses fused multiply-add, reciprocal, and exponential operations for faster computation with native AMD instructions.

The agent optimized code block is written as follows:

__device__ __forceinline__ float silu_f(float x) { const float e = __expf(-x); return __fdividef(x, (1.0f + e)); }

Instruction Interleaving: Alternates SiLU and multiply operations across multiple elements to improve ILP and hide latency.

Tail Optimization: Handles odd H with single-thread computation to avoid divergence.

Occupancy Hint: Control registers and enables more blocks per SM.

The results are shown in the table below:

Optimization Method |

Speedup Ratio |

|---|---|

GEAK Agent optimized |

1.68x |

Manually optimized by kernel engineer |

1.30x |

Table 4: Evaluation of OptimAgent on SwiGLU kernel. Agent optimized speedup compares the performance with the kernel engineer’s result.

The results show that the agent-optimized version significantly outperforms the baseline with a 1.68x speedup, surpassing the engineer’s manual optimization.

Case Study #3: GEMM Heuristic#

General Matrix Multiplication (GEMM) kernels are pivotal in high-performance computing for AI applications, including large language models (LLMs). High-performance libraries like AMD’s rocBLAS and hipBLASLt often rely on offline or online tuning to select optimal kernels. However, such tuning requires exhaustive exploration of hyperparameter spaces and can be prohibitively time-consuming. When tuning is skipped or infeasible due to high computational costs, heuristic approaches provide an efficient alternative by matching kernels to problem sizes (e.g., MNK dimensions) and runtime environments using predefined rules. While heuristics enable real-time kernel selection, poorly designed heuristics can yield suboptimal performance, and crafting effective ones remains challenging due to hardware and application variability.

We propose using the GEAK HIP OptimAgent to enhance heuristic selection by integrating machine-specific information and runtime observations, thereby improving kernel performance and user experience where exhaustive tuning is impractical. As a showcase, we apply this agent to generate heuristics for FP8 GEMM on the MI300x platform, leveraging kernel instances from the Composable Kernel (CK) library [5] backend. In CK, each kernel is defined by a unique combination of parameters such as block and tile sizes, which govern the GEMM computation structure and efficiency. The agent interprets these parameter sets and designs a heuristic rule on top of the provided CK instances.

The major parameters are listed in the table below:

Category |

Parameters |

|---|---|

Data Types |

ABDataType, AccDataType, DDataType, EDataType |

Tile Sizes |

BLOCK_SIZE, MBLOCK, NBLOCK, KBLOCK |

XDL Tile Sizes |

WAVE_TILE_M, WAVE_TILE_N |

Wave Mapping |

WAVE_MAP_M, WAVE_MAP_N |

Element-wise Ops |

CDEElementOp (e.g., RowwiseScale) |

Transfer Ops |

ABLOCK_TRANSFER, BBLOCK_TRANSFER, CBLOCK_TRANSFER |

Shuffle Ops |

CBLOCK_SPV, CSHUFFLE_MX_PER_WAVE_PERSHUFFLE, CSHUFFLE_NX_PER_WAVE_PERSHUFFLE |

Scheduling |

LOOP_SCHED (e.g., InterwavePipeline), PIPELINE_VERSION |

GEMM Specialization |

GEMM_SPEC (e.g., MNPadding) |

Table 5: An overview of CK’s GEMM kernel parameters, categorized into groups.

To enable OptimAgent to generate a heuristic rule, we wrote a unit test, that provides all available kernels to the agent. We then randomly select a few GEMM sizes, covering small to large problem sizes, and use them for runtime latency feedback for the agent to reflect on its heuristic policy.

The key takeaway from the agent generated heuristic rule overview:

// Optimized heuristic-based selector: for all (M,N,K) of small batch/skinny, large batch, or fallback

if ((M <= 128 && N >= 4096) || (M == 1) || (N == 1)) {

// Small batch + wide or batch/vector

return a8w8_blockscale_1x128x128_256x16x64x256_16x16_16x16_16x16x1_16x16x1_1x16x1x16_4_1x1_intrawave_v1<DDataType, EDataType>;

} else if ((M > 128 && M <= 512 && N >= 4096)) {

// Slightly larger batch still wide

return a8w8_blockscale_1x128x128_256x32x256x128_16x16_32x32_8x32x1_8x32x1_1x32x1x8_8_1x1_intrawave_v1<DDataType, EDataType>;

} else if ((M >= 512 && N >= 512 && K >= 1024)) {

// Large and square

return a8w8_blockscale_1x128x128_256x128x128x128_16x16_32x32_8x32x1_8x32x1_1x32x1x8_8_1x1_intrawave_v3<DDataType, EDataType>;

} else if ((M < 256 && N < 256 && K < 256)) {

// Very tiny tiles

return a8w8_blockscale_1x128x128_256x64x64x256_16x16_32x32_16x16x1_16x16x1_1x32x1x8_8_1x1_intrawave_v1<DDataType, EDataType>;

} else if (N <= 128 && M >= 512) {

// Tall and skinny

return a8w8_blockscale_1x128x128_256x64x128x128_16x16_32x32_8x32x1_8x32x1_1x32x1x8_8_1x1_intrawave_v3<DDataType, EDataType>;

} else {

// General fallback

return a8w8_blockscale_1x128x128_256x128x64x128_16x16_32x32_8x32x1_8x32x1_1x32x1x8_8_1x1_intrawave_v3<DDataType, EDataType>;

}

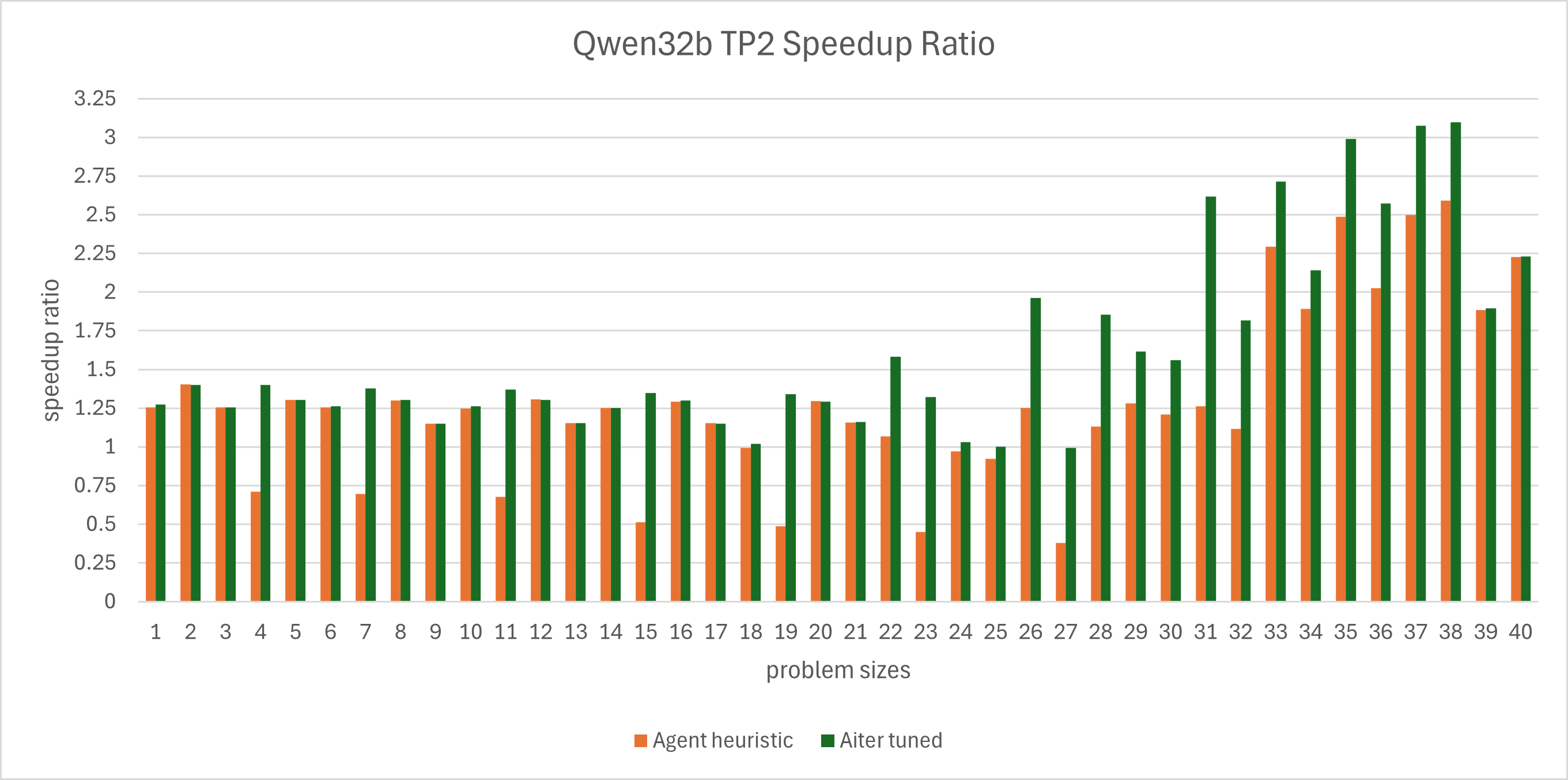

The agent generated heuristics is tested on GEMM problem sizes from the Qwen3-32B model with TP=2 setup, using AI Tensor Engine for ROCm AITER framework [6]. We compare the speedup of the agent generated heuristic against the results obtained from offline tuning in AITER. Detailed speedup ratio (default heuristic latencies vs. tested heuristic latencies):

Figure 2: Qwen32b tensor parallel=2 GEMM speedup ratio over 40 problem sizes.#

From the figure above we can see that:

Overall, the agent generated heuristic speedup ratio vs. AITER original heuristic (all GEMM): 1.28x

Overall, the agent generated heuristic speedup ratio vs. AITER tuned heuristic (all GEMM): 0.8x

Although performance for some problem sizes falls short of AITER’s original heuristic, overall the agent successfully generated a heuristic for Qwen3-32B that matches the fully tuned kernel, demonstrating a successful application.

Summary#

In this blog post, we introduced GEAK for HIP code optimization, an expansion of the original Triton generation GEAK framework to optimize existing HIP code for AMD GPUs such as the MI300X. Powered by frontier LLMs, GEAK employs an AI agent for iterative refinement, featuring three key components: a generator for improved code, an evaluator for compilation and performance testing, and a reflector for error handling. We demonstrated its effectiveness through example benchmarks, including ROCm HIP code examples, MMCV examples, and three case studies (Voxelization, SwiGLU, and GEMM heuristics), all showing substantial performance gains.

This work highlights the growing benefits of automated optimization for AI workloads using the GEAK agent framework. As always, we encourage developers, researchers, and AI enthusiasts to explore the agent and benchmarks, and we hope this sparks broader community collaboration to produce high-performance kernels and ultimately boost AI model training and inference efficiency.

For Triton-based kernel optimization, see our companion blog GEAK-Triton v2: Kernel Optimization for AMD Instinct GPUs , which presents our latest approach to automated Triton kernel generation and optimization.

Additional Resources#

Kernel Agent code: AMD-AGI/GEAK-agent:GEAK-HIP

Previous blog: GEAK: Introducing Triton Kernel AI Agent & Evaluation Benchmarks — ROCm Blogs

References#

rocm-examples [rocm-examples/Applications]

MMCV [open-mmlab/mmcv: OpenMMLab Computer Vision Foundation]

SwiGLU [paper: 2002.05202]

VLLM [vllm-project/vllm: A high-throughput and memory-efficient inference and serving engine for LLMs]

Composable Kernel [ROCm/composable_kernel: Composable Kernel: Performance Portable Programming Model for Machine Learning Tensor Operators]

Biases, Risks & Limitations#

The agent code is being released for research purposes only and is not intended for use cases that require high levels of factuality, safety-critical situations, health, or medical applications, generating false information, or facilitating toxic conversations.

Agent code is made accessible without any assurances of safety. Users must conduct comprehensive evaluations and implement safety filtering mechanisms as per their respective use cases.

It may be possible to prompt the agent to generate content that may be factually inaccurate, harmful, violent, toxic, biased, or otherwise objectionable. Such content may also be generated by prompts that were not intended to produce output as such. Users are therefore encouraged to be aware of this and exercise caution and responsible thinking when using it.

Multilingual abilities have not been tested; therefore, the agent may misunderstand and generate erroneous responses when prompted using different languages.

Acknowledgements#

We would like to acknowledge the following folks for constructive discussions and feedback during this work - Fan Wang, Chang Cui, Ji Liu, Yixiong Huo, Arthur Huang, Fuwei Yang, Mehdi Rezagholizadeh, Stephen Youn, Guihong Li, Vikram Appia, Li Li, Carlus Huang, Peng Sun, Sharon Zhou, Vincent Ouyang, Sina Rafati, and Arseny Moskvichev.

Endnote#

For the statistics shown above, the machine setup follows Configuration #1 for the ROCm statistics example, MMCV examples, Case Study #1, and Case Study #2.

Case Study #3 uses Configuration #2.

System Configuration #1#

AMD Instinct ™ MI300X platform: ORACLE SERVER X10-2c CPU: 2x Intel Xeon Platinum 8480+, 56 cores per socket (112 physical cores, 224 threads) NUMA: 2 NUMA nodes total. auto-balancing disabled Memory: 2048 GiB (32 DIMMs, 4800 mts, 64 GiB/DIMM) Disk: 1x 256 GB BlockVolume (OS disk) + 8× 3.5 TB Intel SSDPF2KX038T1S (NVMe drives) GPU: 8x AMD Instinct MI300X 192GB HBM3 750W Host OS: Ubuntu 22.04.4 LTS BIOS: 79007700 System Bios Vendor: American Megatrends International, LLC. Host GPU Driver: amdgpu/6.10.5-2084815.22.04 ROCm 6.4.3 Firmware: BKC 24.12.10

System Configuration #2#

AMD Instinct ™ MI308X platform: System Model: AS2211TG5 CPU: 2x Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8480C, 56 cores per socket (112 physical cores, 224 threads total) NUMA: 2 NUMA nodes total. auto-balancing disabled Memory: 2.0 TiB total (32× 64 GB DIMMs, Samsung, 5600 MT/s, configured 4400 MT/s) Disk: 2x 447.1 GB SAMSUNG MZNL3480 (OS disk) + 4x 3.5 TB SAMSUNG MZQL23T8HCLS-00BAL (NVMe SSDs) GPU: 8x AMD Instinct MI308X, 206 GB HBM3 per GPU Host OS: Red Hat Enterprise Linux 8.6 (Ootpa) BIOS: 3.0.ES.AL.P.070.30 System Bios Vendor: American Megatrends International, LLC. Host GPU Driver: amdgpu/6.12.12 ROCm 6.4.3 Firmware: BKC 25.01.00

Disclaimers#

Third-party content is licensed to you directly by the third party that owns the content and is not licensed to you by AMD. ALL LINKED THIRD-PARTY CONTENT IS PROVIDED “AS IS” WITHOUT A WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. USE OF SUCH THIRD-PARTY CONTENT IS DONE AT YOUR SOLE DISCRETION AND UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES WILL AMD BE LIABLE TO YOU FOR ANY THIRD-PARTY CONTENT. YOU ASSUME ALL RISK AND ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY DAMAGES THAT MAY ARISE FROM YOUR USE OF THIRD-PARTY CONTENT.